Examining the fall out from Liberation Day and where we go from here

“Liberation Day” was touted as a historic day that Americans would never forget. The announced tariff increases from President Trump on Wednesday certainly lived up to the hype, particularly for investors.

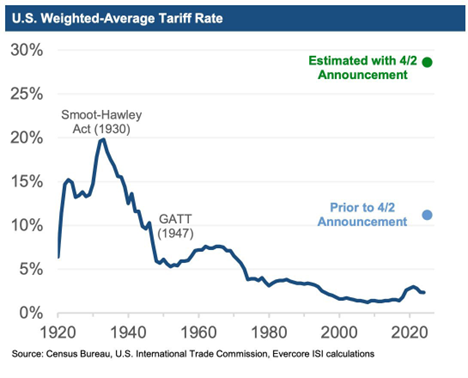

Many of you have seen the headlines and the tariff figures signed into law, so we will not rehash every data point here. The below chart from Evercore summarizes the impact of the Liberation Day tariffs on the effective tariff rate imposed on US trade partners, which in sum would be the highest in over 100 years, and far higher than most market participants expected:

Where does the trade war go from here?

The question on everyone’s minds is: what happens now? The best framework I can apply is what economists and geopolitical strategists call the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a term first coined during the Cold War but is applicable to the current state of this trade war.

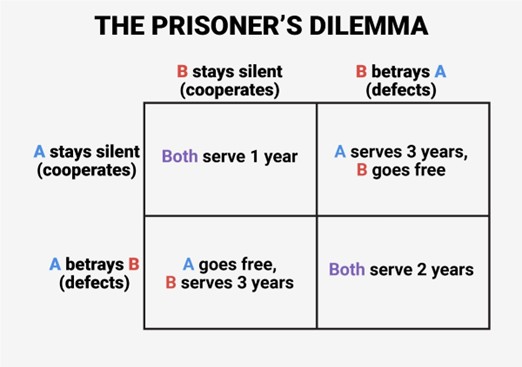

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a scenario where two prisoners who committed a crime together are faced with a decision on whether to stay silent about their crime or confess. Each prisoner is independently questioned by the authorities, and they do not know what the other prisoner will do. The rules, which are known by each prisoner ahead of time, are as follows:

If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison.

If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa).

If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on a lesser charge).

Both prisoners, if they are self-serving, will betray the other prisoner and be set free. However, if they both betray each other, both prisoners are worse off. If both parties cooperate, the end result is better in aggregate for both parties.

Disclaimer – we are not recommending that any criminals lie to law enforcement.

This is the state of affairs in current trade policy. The US has imposed astronomical tariffs on its trading partners. Many of these trading partners are certainly considering retaliation against the US with higher tariffs of their own. They may also feel that they should not trade with the US anymore.

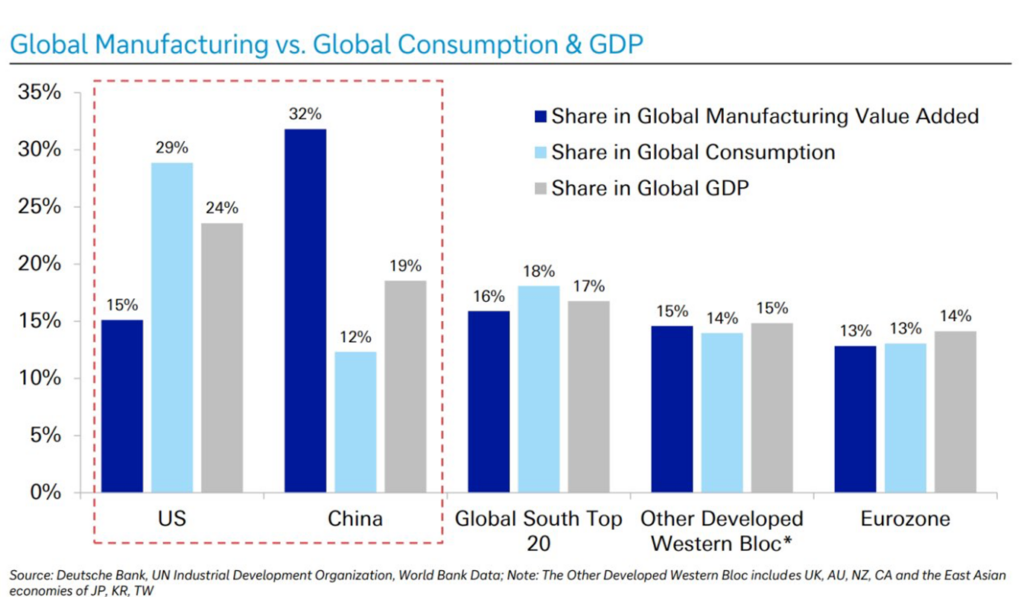

But can they afford to do that? The data suggests that retaliation would be a mutually destructive response, as the US makes up 29% of global consumption (shown in the light blue bars below). In other words, if a country decides to stop selling goods to the US, or increase their tariffs on US goods as a response, companies in that country will have to increase their exports to other trading partners by 30% to make up the difference.

The US is the largest purchaser of goods from the European Union, Canada, Mexico, China, Japan, India, Vietnam, and many others, often by a wide margin. Replacing the USA consumer with other customers is simply not possible in the near future.

On the US side, keeping these high levels of tariffs in place will also create economic pain domestically. Imported goods and services equate to 15% of US GDP. While many would love to see a boost to domestic manufacturing in critical areas such as semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and even automobiles, the US has benefitted from importing lower value non-strategic goods such as apparel and basic consumer electronics. There are many instances where importing these goods benefits US consumers, even if the people manufacturing the product are abroad.

Any potential economic benefit from reshoring manufacturing will take years to show positive results given the amount of time it takes to build the facilities and infrastructure required. Further, the US unemployment rate stands at 4%, suggesting there are not enough workers in the US to replace the amount of production we import.

In the meantime, middle and lower income consumers will be unable to afford these higher prices on imports, and may be unable to buy domestically produced goods in their place (I haven’t seen many, if any, US made televisions at Costco lately, and California doesn’t grow enough avocados for you to add guacamole to that burrito at Chipotle). Even if consumers do not pay the higher prices, companies selling goods to the US will be hard-pressed to bear a 29% hit to their profit margins.

With this backdrop, the result of this 29% tariff rate would be a stalemate where consumers simply spend less money, which lowers economic growth and may lead to a recession as well as a hit to corporate profits.

Where does this leave us? The US has an incentive to cut deals with its trading partners, and the US’ trading partners have a very strong incentive to negotiate these tariff rates down. However, there are competing interests at play – no country wants to look weak to its constituents by caving to US demands (we’ve already seen China announce retaliatory tariffs this morning), and the Trump administration will be hard pressed to lower these tariff rates without showing the American people positive results from this exercise.

If both sides cooperate, we end up with the best case scenario (the top left box of the Prisoner’s Dilemma diagram). If neither side cooperates, we end up with the worst-case outcome (the bottom right box of the Prisoner’s Dilemma diagram).

What are the investment implications?

As for how to invest in this environment, the S&P 500 is set to open trading today down -14% from its highs, but is only back to levels we saw in August 2024 (8 months ago). Valuations have come off the boil but are not cheap (the S&P trades at 19x forward earnings, down from 22x at the start of the year), and earnings expectations remain elevated (consensus estimates call for 11% earnings growth, down from 14.6% at the start of the year).

This set of circumstances suggests that if the US and its trading partners do not reach agreements to lower these tariff rates, the market could have much further to fall, as the economic pain from these tariffs is not fully priced into the market (the average bear market experiences a -30% decline, and we’d likely see P/E ratios much lower than 19x). If a series of deals and compromises are made, we could see a modest relief rally, but we still think the market needs more positive catalysts to make new all-time highs.

This leads us to the conclusion that it is not a “back up the truck” moment to buy stocks as the risk/reward profile is not overly compelling, although we are not too far away from finding interesting opportunities if stocks fall another few percentage points. We’d also caution against running for the hills and selling stocks given the sharp correction we’ve already experienced, and the clear incentives for both parties to come to the negotiating table.

Investors who have been sitting on high cash levels waiting for a correction could be well served by dipping their toe in the water, but reserving additional funds if there is another leg down in the market. In fully invested portfolios, investors should ensure they have sufficient liquidity to cover the next 18-24 months of spending needs, and rely on skilled active managers to find pockets of opportunities within the equity market, as there will be winners and losers from this global trade re-ordering.